The digital pound is an IRL security nightmare, Bank of England reveals

Shock research could throw a spanner in the works of government plans to unleash a central bank digital currency (CBDC).

To conspiratorially-minded people, state-backed central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are the stuff of nightmares, offering governments unparalleled abilities to monitor and control citizens' behaviour.

But the powers that be have never cared much about what all those useless eaters think, so are currently going full steam ahead towards the creation of demoninations like the digital pound - citing major advantages for innovation and inclusion.

The Bank of England has argued that its new cyber-readies will "sit alongside, not replace cash" - which means cash-in-hand builders and dodgy high street barbers will still be able to ply a tax-free existence.

It sees a digital pound as serving two major functions:

1) Promoting "innovation, choice and efficiency" in payments. Which, lest ye forget, is an area in which this nation is known as a pioneer. We have a reputation to protect, so we need to be at the front of the pack when it comes to new ideas.

2) Sustaining access to UK central bank money (dosh issued by the Bank of England) to ensure its role as an "anchor for confidence and safety in our monetary system" and "underpin" monetary and financial stability and sovereignty.

Various financial services firms have also claimed that CBDCs can boost inclusion. Which, frankly, is what they always say. What that actually means is that innovation and extended access to financial services make it easier to get more people in debt. Don't tell them we told you.

In some of the more paranoid corners of the internet, critics say the control offered by CBDCs also shows the potential perils. Said too many hurty words online? Produced too much carbon or scoffed too many bits of meat? No more purchasing stuff for you.

Even if the state remains relatively liberal, the lifestyle visibility offered by digital currencies raises a raft of privacy concerns.

Insurance companies may want to use that access to monitor your behaviour, for instance, so that one sneaky pack of cigarettes bought on a drunken Tuesday night back in 2023 will invalidate your family's claim after you die in a plane crash.

The security challenges of offline Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs)

Now the Bank of England has highlighted a major potential problem with the digital pound after conducting IRL (in real life) experiments with "offline payment functionality".

In a paper detailing the trial, the Bank described testing payments in which neither payer nor payee has access to the CBDC network via an internet connection.

The idea was to explore whether offline payments could provide "additional resilience in the event of network disruption or outage of telephony services". And, of course, dig into whether it could "support financial inclusion".

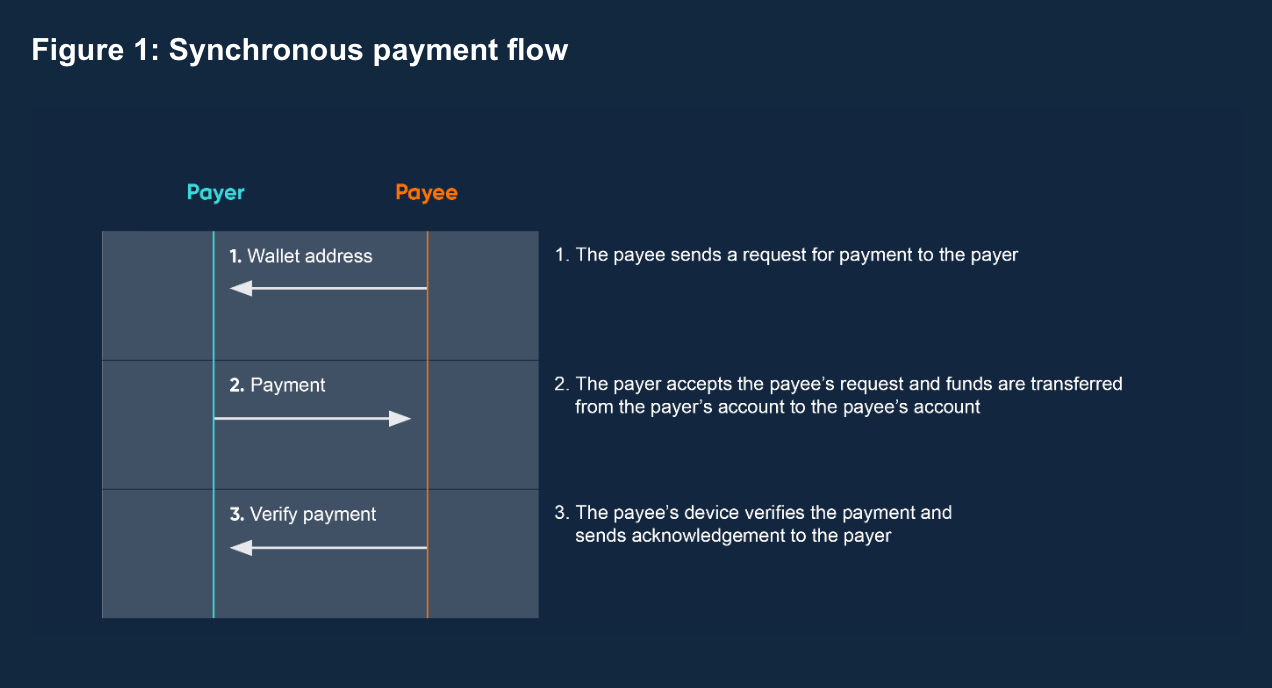

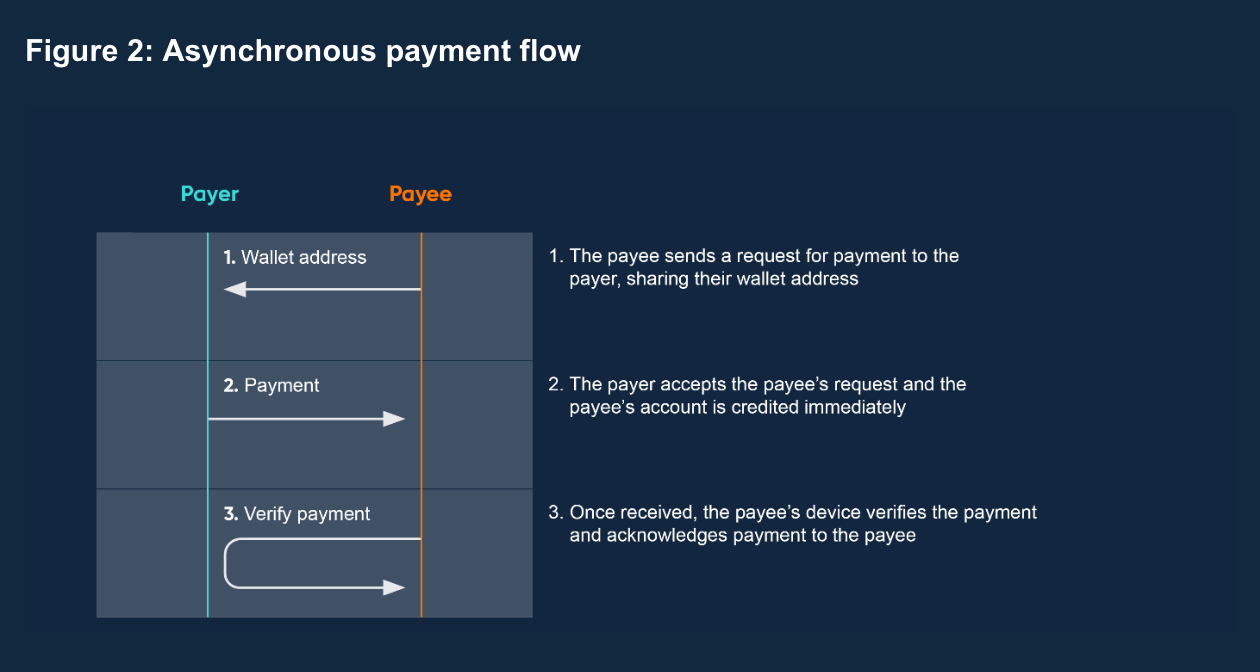

The Bank found it was "technically feasible to make final and irrevocable offline CBDC payments". In other words, offline payments were as final as handing over cash (assuming the payee didn't steal it back).

It achieved immediate confirmation and settlement, enabling the payee to spend funds they received without having to reconnect to the network.

Funds were stored on a user’s smartphone or smart card and then transferred or downloaded from each payment solution’s core ledger to user devices via a payment intermediary. With smartphones, funds were added directly to the device. When using smart cards, money was transferred onto the card via a smartphone’s NFC capability.

So far, so good.

Fake money and false payments

However, the Bank warned that counterfeiting and double spending (using the same funds to make more than one payment) were possible by hacking into the payment systems.

To address security challenges, the tech used in the trial relied on "secure elements" - microprocessor chips with enhanced security protections to prevent unauthorised access, which can be embedded in phones, SIMs and smart cards. Most modern smartphones already have these chips in place.

One approach stored the full offline solution - cryptographic keys and transaction data - in a secure element. The other kept only some of these components in the secure element and the rest in local memory.

Online reconciliation was used as a "fallback security measure" in all four solutions to prevent counterfeiting and double spending.

"Being retrospective, online reconciliation helped to detect and identify counterfeiting and double spending, but it could not prevent either," the Bank of England wrote. "At the point at which online reconciliation happens, users would have already suffered losses."

"Additional countermeasures had an impact on user experience and costs," it continued. "Measures such as risk mitigation limits had a negative impact on user experience since they prevented users from making further payments offline, often unexpectedly.

"There might also be financial inclusion impacts since more expensive, higher-end devices were needed to guarantee stronger security."

Insecure elements

So the problem with offline CDBC payments is that the payee cannot be guaranteed they haven't suffered a fake transaction or a double payment until they connect to the internet - by which time it's too late. The scammer will have scarpered.

"Offline CBDC would be an innovative feature with potential to support different policy goals, such as resilience or financial inclusion," the Bank of England concluded. "This project demonstrated that it might be technically feasible to implement an offline payment functionality for a digital pound but there are security, performance, and user experience challenges which need to be explored further.

"One key area is the security challenges related to double spending and counterfeiting. Heavy reliance on secure elements meant that if the secure elements were breached, double spending and counterfeiting might occur. Secure elements are commonly used in payments today, but they are, in most cases, paired with immediate online authentication, thus limiting losses.

"In contrast, the online layer in an offline payment (online reconciliation) occurs only after the transaction has taken place and losses have already been incurred."

The Bank also noted that there were "policy, operational, legal and commercial considerations" as well as technical issues that were not addressed in its experiment, such as "what happens to offline funds if a user loses their device."

There was a bit of good news which should calm the fevered minds of conspiracy theorists.

Privacy-enhancing technologies were applied to protect personal data when users reconnected to the network.

The Bank was able to safeguard personal data when users reconnected to the network to share transaction records with payment intermediaries without the demonstration core ledgers gaining access to personal data.

It achieved this using data pseudonymisation, ephemeral key management and confidential computing.

"Using these technologies, it was technically feasible to store an offline transaction record while protecting personal data when users reconnected to the network," the Bank wrote.

The research confirmed that offline CBDCs are a potential security nightmare but probably not a major privacy concern.

And we're sure security issues can be solved, so perhaps it's time we stopped worrying and learned to love CBDCs.

Or is it? Let us know at the address below.

Have you got a story or insights to share? Get in touch and let us know.