Earth could be overdue for apocalyptic once-a-century solar superflare

"New data is a stark reminder that even the most extreme solar events are part of the Sun's natural repertoire."

Scientists have discovered that Sun emits devastating solar storms at least once a century. And it's been 164 years since the last one...

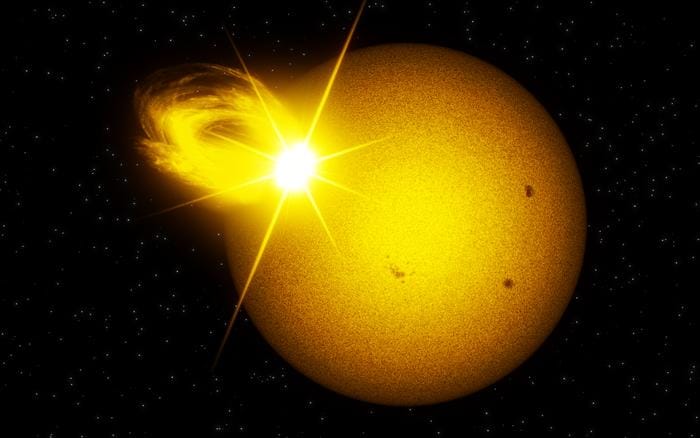

Mild solar storms are regular occurrences, causing the Northern Lights to be visible even from low latitudes.

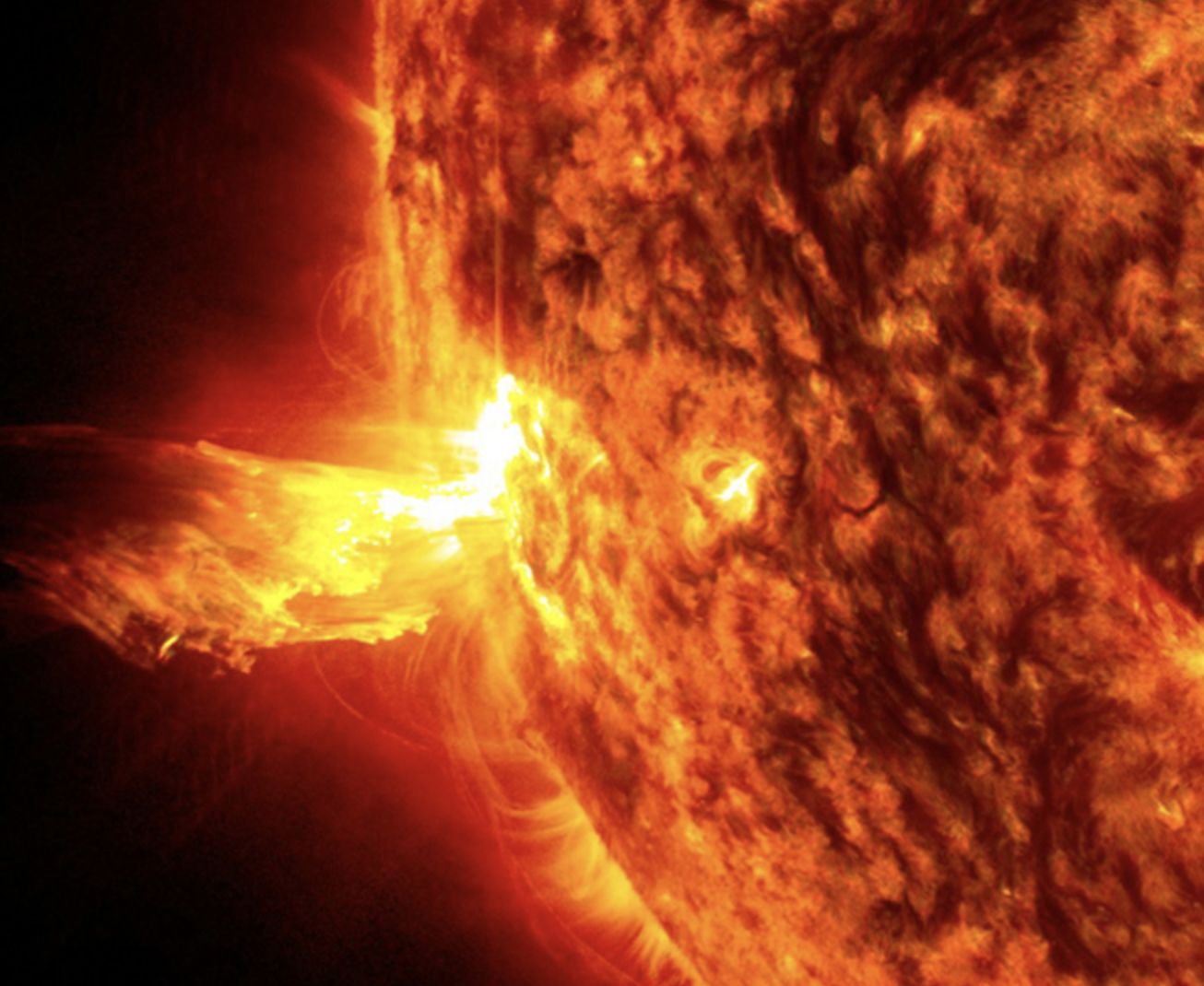

But sometimes our star can "become even more furious" and throw "violent solar 'tantrums'" that bathe large swathes of the planet in radiation, the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) warned.

Traces of these stellar outbursts are locked away in prehistoric tree trunks and in samples of millennia-old glacial ice. Yet to understand the frequency of apocalyptic solar mega-flares, a team from the Insitute looked upwards for answers.

“The new data are a stark reminder that even the most extreme solar events are part of the Sun's natural repertoire,” said co-author Dr Natalie Krivova from the MPS.

During the Carrington event of 1859, one of the most violent solar storms of the past 200 years, the telegraph network collapsed across northern Europe and America as fires erupted in transmission stations. The burst that caused this incident released one-hundredth of the energy of a superflare.

If a full-force flare were to hit us, X-rays and gamma rays would strip Earth’s upper atmosphere and damage satellites. The eruption would disrupt radio communication and GPS systems, as well as giving orbiting astronauts a nasty dose of radiation.

In extreme cases, superflares could potentially destroy the ozone layer, exposing life to dangerous UV radiation. However, whilst superflares from the sun are theoretically possible, they are less likely than with younger, more active stars. So we should be safe from being zapped into oblivion, but would probably experience severe economic damage if a flare fried telecommunications networks across the planet.

How can we predict the arrival of the next superflare?

We can't precisely. Indirect sources here on Earth will not let us determine the frequency of superflares. But another way to learn about our Sun’s long-term behaviour is to turn to the stars and examine their brightness fluctuations in visible light.

In a short space of time, superflares unleash more than one octillion joules (enough to power humanity for a few million years, according to ChatGPT's calculations). This shows them in the observational data as short, pronounced peaks in brightness.

“We cannot observe the Sun over thousands of years,” Prof. Dr. Sami Solanki, co-author and Director of the MPS. “Instead, however, we can monitor the behaviour of thousands of stars very similar to the Sun over short periods of time. This helps us to estimate how frequently superflares occur,” he adds.

In the current study, a team including researchers from the University of Graz (Austria), the University of Oulu (Finland), the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, the University of Colorado Boulder (USA) and the Commissariat of Atomic and Alternative Energies of Paris-Saclay and the University of Paris-Cité, analyzed the data from 56450 sun-like stars imaged by NASA’s space telescope Kepler between 2009 and 2013.

“In their entirety, the Kepler data provide us with evidence of 220000 years of stellar activity,” said Prof. Dr. Alexander Shapiro from the University of Graz.

Stars were chosen to be particularly close “relatives” of the Sun, which meant that they must have similar surface temperature and brightness.

The researchers also ruled out sources of error such as cosmic radiation, passing asteroids or comets, as well as "non-sun-like stars" that may flare up by chance in the vicinity of a sun-like star. To do this, the team carefully analyzed the images of each potential superflare - only a few pixels in size - and only counted events that could be reliably assigned to one of the selected stars.

Thet identified 2889 superflares on 2527 of 56450 observed stars, showing one sun-like star produces a superflare roughly once every century.

“We were very surprised that sun-like stars are prone to such frequent superflares”, said first author Dr. Valeriy Vasilyev.

Countdown to cataclysm: The frequency of superflares

Earlier surveys by other research groups had found average intervals of a thousand or even ten thousand years. However, these studies were unable to determine the exact source of the observed flare and were limited to stars that did not have any uncomfortably close neighbours in the telescope images. The current study is the "most precise and sensitive to date",

When a high flux of energetic particles from the Sun reaches Earth's atmosphere, the collision produces radioactive atoms as carbon isotope14C, which are deposited in "natural archives" such as tree rings and glacial ice, where they can be found thousands of years later.

In this way, researchers identified five extreme solar particle events and three candidates within the past twelve thousand years of the Holocene, leading to an average occurrence rate of once per 1500 years.

The most violent is believed to have occurred in the year 775 AD, which appears to have largely unnoticed (but please do let us know if you know differently). However, it is quite possible that more violent events and superflares occurred on the Sun in the past.

“It is unclear whether gigantic flares are always accompanied by coronal mass ejections and what is the relationship between superflares and extreme solar particle events," said co-author Prof. Dr. Ilya Usoskin from the University of Oulu. "This requires further investigation."

The new study does not reveal "when the Sun will throw its next fit". But it is a call for urgent action to forecast superflares and take precautions such as switching off satellites.

From 2031, ESA’s space probe Vigil will help to monitor space weather by keeping an eye on the action brewing up on our star. The Max Planck Institute is also currently developing the Polarimetric and Magnetic Imager for this mission.

Have you got a story to share? Get in touch and let us know.